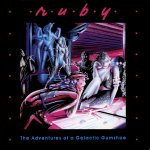

The 25th anniversary of Blade Runner has stirred up some thoughts on a subject that is becoming more and more relevant with each passing year, or perhaps more accurately with each new leap in technology. From the time Mary Shelley penned Frankenstein, science fiction has examined not only what makes us human (which is arguably what most fiction is about), but what makes our creations "human." When does a created being--a "monster", clone, robot, android, holographic projection, artificial intelligence--cross over and become, if not "human", then a person worthy of being granted the ever-elusive prize of "human" rights? Considering that many people on this planet have not yet achieved this status, it is no surprise that some people would have difficulty granting rights to something created by humans. Even some science fiction-minded individuals who have no difficulty recognizing aliens as "people" -- even those aliens so dramatically different from human as to be almost unrecognizable as "human", like a silicon-based lifeform, for instance-- find granting the same status to a created being problematic. The argument runs, as I understand it, that if something is created and programmed and what-have-you, it is a thing and not a person, no matter how much it may think, act, or look like a human. As my favorite galactic gumshoe puts it (referring to a damaged android who has been crying), "She's programmed to say she hurts!"

I find this question of sentience puzzling, for I am certainly not suggesting we grant "personhood" to pocket calculators and cell phones. Up to a point, the above argument is correct, at least concerning technology as we know it today. If you have ever had a conversation with an AI (they have them at various places online and some art exhibits), you'll know what I mean. I have had some frustrating encounters with such creatures and find them to be very stupid machines. But I digress.

What science fiction makes possible is the taking of an idea or a technology or both and projecting them out to a possible conclusion. As in the case of Blade Runner, what would happen if we were so successful in creating an artificial human, an android, that it took on a life of its own, developing memories, experiences, a range of emotions, and most especially, a desire to live? Other characters in movies and television who explore this idea are Data (Star Trek: Next Generation), the Doctor (Star Trek: Voyager), Terminator (Terminator 2), and David (A.I.). I'm sure there are more. And in books, of course, the list is endless; however, the master of them all would be Isaac Asimov. I recommend the novella "Bicentennial Man" and "Kid Brother," one of Asimov's short stories, among many others.

What fascinates me is the moment of transition: When does an android go from a collection of programmed knee-jerk reactions to a person? How does it happen? And why? Is this what we call a "soul"? Is this how new sentience evolves? It's about more than just intelligence; intelligence cannot be the only factor. My list for defining sentience is as follows (subject to revision):

self-awareness

creative expression

emotions/empathy

ability to dream and to wish

ability to learn

desire to live

I have not decided if one must possess all, or some, or at least two from the above list to be considered sentient. Something to think about.

Wikipedia has an interesting article on Sentience, if you're interested. In short, it says, "Some science fiction uses the term sentience to describe a species with human-like intelligence, but a more appropriate term for intelligent beings would be 'sapience'." The article also includes "free will" and "ability to experience suffering" in addition to some of those items I listed above.

More important, perhaps, than the "when" and "how" and "why" sentience/sapience develops is our own internalization of that process. Our attitude towards the Other determines our own humanity: When we deny sentience/sapience to an obviously sentient/sapient being, it is we who are diminished, not the opposite.

Deckard is astonished when Roy Batty saves his life. Had the situation been reversed, Deckard would have had to follow through with his orders to "retire" the android. In the end, it is the android that teaches the man a lesson in what it means to be human. For with his own death closing on him rapidly, Batty treasures each moment, each memory, and life itself.

"I have seen things you people wouldn't believe:

Attack ships on fire off the shores of Orion;

I've watched c-beams glitter in the dark near Tanhauser Gate.

All these moments . . . lost . . . in Time . . .

like tears in the rain."

22 Days til Lift-Off

No comments:

Post a Comment